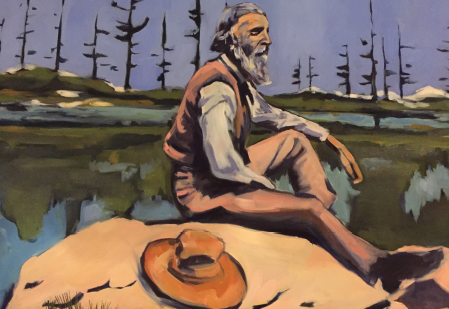

Before thousands of climbers ascended Mount Whitney every year, a group of Buffalo Soldiers reached the summit in 1903. The first African Americans to climb the mountain also built its first summit trail. Enthralled by the grand scenery, Captain Charles Young committed to “preserving these mountains just as they are.”

Under Young's command, Buffalo Soldiers protected Sequoia National Park's big trees, guarded against poachers and prevented illegal grazing. Sadly, the nation all but forgot them for a century. Yet the same park honored Confederate General Robert Lee, naming a giant sequoia for a traitor who fought to keep such men in slavery.

This is no isolated problem. A California map reads like a badly-flawed history book, full of places named for 19th Century white men to the exclusion of nearly everyone else. Lee isn’t the only white supremacist to win a geographic honor. Women and people of color are rare, women of color especially so. Indian killers drastically outnumber Indians, and original indigenous names are nearly forgotten.

But here’s a piece of good news in a tough year. Following the Minneapolis police killing of George Floyd in May, a revived national civil rights movement has promoted a map makeover, with multiple geographic name changes approved or proposed in California alone.

Jeff Davis Peak near Lake Tahoe, which honored the Confederates’ president, in July officially became Da-ek Dow Go-et Mountain. The Washoe Tribe proposed the new name which the federal government approved.

California State Parks is considering a new name for Negro Bar in Folsom Lake State Recreation Area, where African American miners prospected for gold in 1850.

Alabama Hills National Recreation Area, named by Confederate sympathizers for a rebel warship, will change names if the nonprofit Friends of the Inyo has its way. The Bureau of Land Management is considering the suggestion.

The name of Portagee Joe Campground in Lone Pine contains an anti-Portuguese slur, claims attorney Allen Berrey, who is pursuing a change.

Preceding 2020’s upheaval, Squaw Ridge in Mokelumne Wilderness was renamed Hungalelti Ridge as the Washoe suggested in 2018. After considering the racist writings of Joseph LeConte, Yosemite renamed LeConte Lodge as Yosemite Conservation Heritage Center in 2016. And Santa Monica National Recreation Area renamed a peak as Ballard Mountain, honoring a Black pioneer and replacing an outrageously offensive slur on the map in 2010.

Outdoors enthusiasts should welcome these changes. We who often enjoy public lands know that the outdoor-loving public is much less diverse than our overall population. People of color visit national parks in low numbers; African Americans tally just one percent of Yosemite visitors, for example. Taking steps to make more feel welcome hurts no one. It’s simply the right thing to do.

Clearly the map needs more diversity, but what about the likes of James Beckwourth? A Sierra Nevada pass and mountain honor the biracial American from Virginia who survived slavery and moved west. Yet he brags in his autobiography about killing Indians and striking his wife in the head with an axe.

In a world of flawed people, where do we draw the line?

I can’t answer that, but I’m certain we have far to go before going too far. So, I’m glad to see well-intentioned people trying to promote sensitivity, diversity and inclusion in the outdoors.

Charles Young would be happy too, I suspect. The first African American national park superintendent, Young wrote of a future in which “overworked and weary citizens of the country can find rest” in the outdoors. He and his Buffalo Soldiers helped make that vision a reality.

A century later, Sequoia National Park named one of its magnificent trees for him. Last year, a Colonel Charles Young Memorial Highway followed. This year, the National Park Service removed references to slave-owning Robert Lee from trees in the mountains Young protected.

To that, this descendant of Civil War soldiers says, “Huzzah!”

— Matt Johanson authored the new guidebook, “Sierra Summits: A Guide to 50 Peak Experiences in California’s Range of Light.”