He came in obscurity as a teenager and ended up teaching school in the bustling foothill gold mining burg. In less than a year he was leaving La Grange dead broke but rich in experiences that he would craft into stories that would launch him into immortality as one of the great classic writers in American literature.

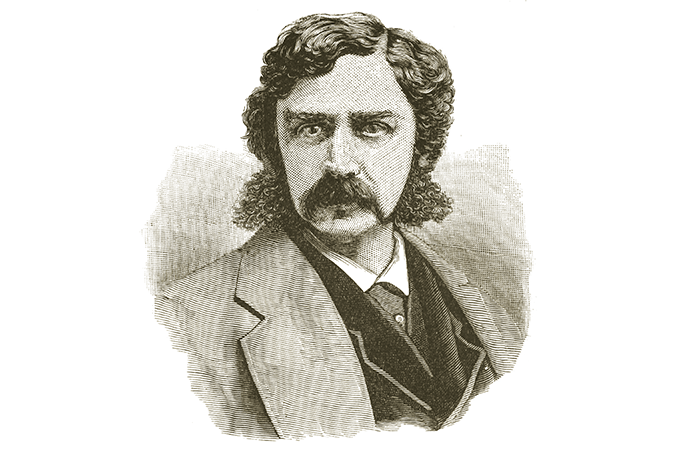

Francis Bret Harte was touched by La Grange, the tiny hamlet located up the Tuolumne River in eastern Stanislaus County. But his exploits throughout Northern California are evident by the numerous schools, parks, streets and one town named for him.

The father of local color stories, Harte made a name for himself by taking his observations of people, their language, habits and customs and turning them into short stories of humor and substance. His exploits in the Mother Lode gold country would become synonymous with those of Samuel Langhorne Clemens, best known as Mark Twain, as both grew in literary stature simultaneously. Their last names are linked and immortalized in the name of Twain Harte in Tuolumne County — though there’s no evidence that either men stepped foot there.

Born to a literary critic mother and a teacher father on Aug. 25, 1836 in Albany, New York, Harte first showed an interest in writing at the age of 11. A poem he submitted to the New York Sunday Atlas was published marking the start of his writing career. His formal education ended at age 13 but his ravenous appetite for books from his father’s library continued. When Harte was nine, his father died, leaving the family without financial support and at the mercy of relatives. Harte’s mother embarked for California in 1853, ending up in Oakland, where she eventually remarried.

On Feb. 20, 1853, (some reports list 1854) Harte boarded a steamer ship bound for San Francisco to join her.

“I went by way of Panama and was at work for a few months in San Francisco in the spring of 1853,” Harte wrote later.

Working as an apothecary at Sanford’s Drug Store in Oakland, young Harte grew restless. “I felt no satisfaction with my surroundings until I reached the gold country, my particular choice being Sonora in Calaveras County,” wrote Harte. Sonora, it should be noted, is now in Tuolumne County.

According to the 1931 biography, “Bret Harte: Argonaut and Exile,” by George Stewart Jr., Harte’s life went largely unrecorded between March 26, 1854 and March 1, 1857. Stewart writes: “...in this period the legendists and the counter-legendists have long made free. The former have declared Harte the two-gun hero of a western epic; the latter have called him an effeminate young ‘squirt’ who never even entered the mining country.”

The latter were obviously wrong.

Some historians believe that Harte ended up in La Grange during 1855. That he could be hired as a school teacher with no serious education and being only a teenager was not implausible. In fact, the state Superintendent of Public Instruction often complained that children were being taught by teachers who themselves should have been in school.

La Grange had a school as early as 1854 as the town merchants, businessman and miners had children who were in need of an education. La Grange began as French Bar, a camp settled by French miners in 1849. When the floods of the winter of 1851-52 wiped out the low-lying village along the Tuolumne River, the town site was relocated a mile upstream on higher ground where present-day La Grange sits. The town’s name changed from French Bar to La Grange (French word for barn) by late 1854.

The impeccably dressed, faintly mustachioed Harte likely arrived in La Grange by way of stage from Sonora, quite possibly crossing through Knights Ferry, Cooperstown (which no longer exists) and across a Tuolumne River ferry. Harte likely marveled at what he saw for the town was at its zenith with the busy traffic of gold mining and was a good deal larger than one would expect for a two-year-old town.

Over the years, some historians have suggested that Harte may have taught instead at Don Pedro Bar, east of La Grange on the Tuolumne River; or possibly at Jacksonville, a mining town not far from La Grange but was abandoned to a watery grave with the raising of the Don Pedro Dam in 1970. Stewart believes La Grange makes sense. His “M’liss” story was first called “The Work on Red Mountain.” An actual Red Mountain is but a few miles above La Grange.

Harte did not teach in the historic old La Grange schoolhouse standing on the hill overlooking La Grange as it was built in 1875 decades after Harte left. However, the town had an early adobe schoolhouse where Harte may have taught.

It is believed that Harte arrived late in the school year at La Grange as his name doesn’t appear in early county school records on file with the clerk of the Stanislaus County Board of Supervisors.

Harte did not stay in La Grange beyond a year but his experiences there formed a battery of ideas, which later served to drive Harte to the pen and quill and let his literary talent run free. In 1860 Harte published “The Work on Red Mountain,” based on his experiences as a schoolteacher. Harte crafts the town of Smith’s Pocket in his story. His work was later expanded into a much longer piece titled “The Story of M’liss,” in which a young social outcast Melissa Smith comes to the schoolmaster and requests that he tutor her. Harte may have fabricated the character based on La Grange personalities. Harte opens the story: “Just where the Sierra Nevada begins to subside in gentle undulations, and the rivers grow less rapid and yellow, on the side of a great red mountain stands Smith’s Pocket. Seen from the red road at sunset, in the red light and the red dust, its white houses look like the outcroppings of quartz on the mountain side.”

It appears that the school teacher in ‘M’liss” was Harte himself as he expressed contempt for the people of La Grange. A product of the refined East Coast, Harte was a fashion plate that stood out from the locals. He said the “greater portion of the population to whom the Sabbath, with a change of linen, brought merely the necessity of cleanliness without the luxury of adornment.”

It’s also believed that La Grange contributed to “Cressey,” “The Tale of Three Truants,” and “How I Went to the Mines.” His 1903 short story, “A Sappho of Green Springs: The Four Guardians of La Grange” is probably ginned up between experiences at La Grange and a Green Springs, a once-thriving settlement off of La Grange Road near Highway 120 that has disappeared and marked by a Clamper’s monument plaque.

Did the incidents Harte wrote about actually happen or were they crafted out of Harte’s fertile imagination? No one can be sure although Harte said of his works: “My stories are true, not only in phenomena but in character. I do not pretend to say that many of my characters existed exactly as they are described, but I believe there is not one of them that did not have a real human being as a suggesting and a starting point. Some of them, indeed had several...”

Harte wrote that when prominent families left town, the school closed and he was out of a job in May. Biographer Stewart believes that was in 1855. Harte wrote later that he abandoned “a peaceful vocation for one of greed and adventure.” He also stated that his “initiation into the vocation of gold digging was partly compulsory” for he was broke.

With only two bucks in his pocket after buying a $5 pistol, he spent two days walking in patent leather shoes through red dirt toward the Sonora area, perhaps along what is now La Grange Road or Jacksonville Road into Jamestown or the road to Chinese Camp. His duded-up appearance must have been cause for attention. For one thing, he wrote that his revolver “would not swing properly in its holster from my hip but worked around until it hung down in front like a Highlander’s dirk, gave me considerable mortification.”

Harte noted that at sunset on the second day he came to an “unfathomable abyss,” no doubt the Stanislaus River canyon. He spotted a mining camp on the other side and settled down. Stewart suggests that this was Robinson’s Ferry, a settlement later on Highway 49 south of Carson Hill and Angels Camp (the site was covered by waters of New Melones Reservoir.) There Harte tried his hand at gold prospecting. He spent time in Tuttletown and Jackass Hill with brothers James and William Gillis in the same cabin Mark Twain would later visit. If Jim Gillis is correct, a man named Harte and walking in latent leather shoes – which were killing the young man’s feet – stopped by the cabin in December 1855.

Harte’s stories, “Plain Language from Truthful James” and “The Heathen Chinee” took place there and possibly based on Gillis, who was a pocket miner. “The Luck of Roaring Camp” was inspired by his experience in the gold country as Roaring Camp was a town on the Mokelumne River in Amador County.

Like thousands who became disillusioned from prospecting and finding nothing larger than a $12 nugget, Harte left for Oakland broke and without money for stage fare. Harte was back in Oakland in 1856, living at Clay and Fifth streets (now in the shadow of the Nimitz Freeway.) He later took on tutoring the four sons of Abner Bryan near the base of Mt. Diablo as the cattle rancher did not care to have the boys “grow up like range-cattle.” Some believe Harte drew upon his experiences in Alamo in his stories, “A Legend of Monte Diablo,” “Cressy, The Convalescence of Jack Hamlin” and “A First Family of Tassajara... The Queen of the Pirate Isle.”

Harte was working for the U.S. Surveyor-General’s Office in 1862 when he wrote “Notes by Flood and Field,” and mentioned the 1861-62 flooding of the San Joaquin Valley which created a massive but short-lived lake stretching from Stockton to Merced.

Harte later served as a messenger for Wells Fargo Company, riding beside the stagecoach driver. His fear of being gunned down during a stage robbery as evident as he told a reporter in his later years: “Stage robbers were plentiful. My predecessor had been shot through the arm and my successor was killed.”

In 1857 he went to Humboldt County where his sister was living. He became an apprentice press operator, or “printers’ devil,” for the “Northern Californian” newspaper.

Harte didn’t go headlong into writing until he returned to San Francisco in 1857 to become a typesetter for the Golden Era newspaper. His first version of M’liss appeared in print that year, creating an interest in his works.

He gradually became a writer and editorialized about a massacre of Indians in 1860. His support of Indians and Mexicans proved unpopular with the locals and he was advised to leave town.

After marrying Anna Griswold in 1862 in San Rafael, Harte became the secretary of the California Mint. Two years later Harte met Mark Twain. Harte was immediately impressed with the sarcastic young reporter fresh from Virginia City who sported black curly hair, black bushy eyebrows and “an eye so eagle like that a second lid would not have surprised me.” Harte claimed that he prompted Twain to write the fanciful story of “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” which brought fame to Twain. It is said that Harte’s M’liss influenced Twain directly in Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn stories.

From 1868 to the early part of 1871 he served as editor of the Overland Monthly, a San Francisco publication.

Harte led an amazingly complex and interesting life and spent his final years in England. He died in 1902 and is buried at St. Peter’s Church in Surrey, England under a slab of marble engraved with “Death shall reap the braver harvest.” It is a phrase that Harte wrote himself in “The Reveille.”