In a little-visited northeastern corner of California, just south of the Oregon border, you can go cave-tubing. Not in the sense of riding an inner tube in a cave river, but rather exploring an extraordinary collection of caves created by lava tubes from basaltic lava that flowed across the landscape over 10,000 years ago.

Hollow hills

To visualize the formation of these lava tubes, think of the lava you have seen flowing in Hawaii on its journey into the sea. As the exterior of the lava encounters the air, it hardens, but the fiery hot liquid lava continues to advance within. When the lava no longer flows, left behind are long tubes – or caves.

Over the millennia, tubes formed on top of other tubes, creating a labyrinth. The actual number of caves is unknown, but estimates range from 200-400. Of these, over 30 are open to the public for exploration.

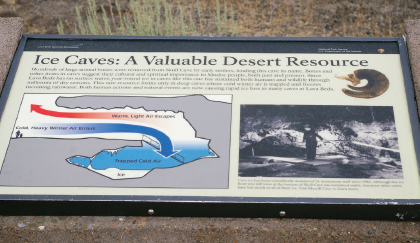

Caves of many uses

For centuries, the Modocs used many of the caves as campsites and sacred sites. Prehistoric tribes also used the caves and ancient petroglyphs dot some of the walls.

In 1888, Tom Durham made the first known historic account of what would become Bearpaw Cave. However, the discovery of the cave system is credited to J.D. Howard. He came to the Klamath region in 1916, and for over 20 years explored and opened up many of the caves.

Set aside as a national monument in 1925, in 1933 Lava Beds was transferred to the National Park Service. As tourists began to visit, and with the Great Depression in full swing, Federal Work relief projects with the Civilian Conservation Corps were implemented to improve the caves and make them more accessible, without damaging their natural features.

Helmets advised

Mushpot Cave is the easiest cave to visit, particularly if you’re not keen on caves, and is often used for interpretive presentations. Softly lit, you have the opportunity to see the layers of tubes through roof gaps, and myriad types of lava formations. Look for lavacicles (lava icicles) and cauliflower lava clumps. Walking the pathway, you’ll pass remnants of a moonshine still. The path ends to leave you gazing into the dark bowels of the cave.

Note that with the exception of Mushpot, none of the caves are lit, and you are advised to borrow helmets at the Visitors Center – known as “bump hats” – and powerful flashlights to enable you to explore the many caves situated right there at Cave Loop. Rangers also recommend you wear long sleeves, pants, and close-toed shoes or boots. The climate inside the caves is often cool and damp, and rough lava protrusions can make for some bumpy going.

The caves range from easy to extremely challenging with crawling and scrambling. Some are just a few hundred feet long, such as Skull and Heppe; others are extensive, such as the nearly 7,000-foot Catacombs or the 2,200-foot Golden Dome, Hercules and Juniper caves. At the Visitors Center, pick up a cheat sheet which will allow you to select the caves best suited to your interests and stamina.

Otherworldly

Some caves are reached by hiking across rocky terrain among scrubby juniper trees. You will pass roof collapses or see swells and ridges hinting at other tubes. Except for an occasional bird and the hiss of wind across sand, you feel as if you were on a forgotten piece of our planet. Lava Beds is truly a unique adventure, a reminder of the West Coast’s explosive volcanic past. Note that some caves may be periodically closed – it’s wise to check current info at bit.ly/LAVAbeds.